Diana Deutsch - ddeutsch@ucsd.edu

Department of Psychology

University of California San Diego

La Jolla, CA 92093, USA.

Kevin Dooley

Department of Psychology

University of California San Diego

La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

Trevor Henthorn

Department of Music

University of California, San Diego

La Jolla, CA 92093, USA.

Brian Head

Thornton School of Music

University of Southern California

Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA.

Popular version of paper 4aMU1.

Presented Thursday Morning, May 21, 2009

157th ASA Meeting, Portland, OR

Absolute pitch, otherwise known as ‘perfect pitch’, is the ability to name or produce a musical note of particular pitch without the aid of a reference note. This ability is generally considered extremely rare, with an estimated overall prevalence of less than one in ten thousand. Because of its rarity, and because many famous musicians were known to possess it, absolute pitch is often regarded as a mysterious genetic endowment. We here report a study showing, for the first time, that the probability of acquiring absolute pitch is strongly influenced by the language spoken by the listener, with genetic factors held constant. These findings have strong implications for scientists seeking to understand the basis of absolute pitch.

We explored the prevalence of absolute pitch among students at the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music. There were 203 subjects in the study, 110 male and 93 female, with average age 19.5 years. All those who were invited to take the test agreed to do so, so there was no self-selection of subjects for the experiment. The subjects filled out a detailed questionnaire concerning their music education, ethnic heritage, where they and their parents had lived, the languages they and their parents spoke, and how fluently the subjects spoke each language.We gave the subjects a test of absolute pitch consisting of the 36 notes that spanned the 3-octave range beginning on the C below Middle C, with all intervals between successive notes greater than an octave. The notes were piano tones generated on a Kurzweil synthesizer and recorded on CD. The subjects listened to the CD through loudspeakers, and identified each note in writing.

The following is a brief test with notes designed as in the experiment.

Click here (MP3 file) to listen

to the brief test.

Click here to view the answers.

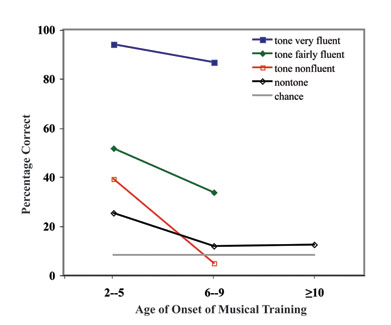

Based on their responses to the questionnaire, we divided the subjects into four groups. Those in group nontone were Caucasian and stated that they spoke only a nontone language such as English fluently. The remaining subjects were all of East Asian descent, with both parents primarily speaking an East Asian tone language. These were assigned to three groups in accordance with their responses to the questionnaire. Those in group tone very fluent reported that they spoke an East Asian tone language ‘very fluently’. Those in group tone fairly fluent reported that they spoke a tone language ‘fairly fluently’. Those in group tone nonfluent, responded ‘I can understand the language, but don’t speak it fluently’. We further divided each group into two subgroups based on age of onset of musical training: One subgroup had begun musical training at ages 2-5, and the other at ages 6-9. (A third subgroup of nontone language speakers had begun musical training at the age of 10 or later, but since all the East Asian students had begun musical training before or at age 9, the data from this third subgroup were not compared statistically with the others.)

The figure below shows, for each group and subgroup, the average percentage correct on our test for absolute pitch. The line labeled chance represents chance performance on the test. We can see that, within each group, those subjects who had begun musical training at ages 2-5 scored higher than those who had begun training at ages 6-9. However, there was also an overwhelmingly strong effect of tone language fluency, holding ethnicity constant. Those subjects who spoke a tone language very fluently showed remarkably high performance on the test, with an overall performance of over 90%. Indeed, their performance was far higher than that of the Caucasian nontone language speakers, and importantly it was also far higher than for the subjects of East Asian ethnicity who did not speak a tone language fluently; i.e., the tone nonfluent group. And it was also higher than that of the tone fairly fluent speakers, which was in turn higher than that of the tone nonfluent speakers, and of the nontone language speakers.

On statistical comparisons, the performance of the (East Asian) tone very fluent group was significantly higher than that of the (Caucasian) nontone group. But importantly, it was also significantly higher than that of the (East Asian) tone nonfluent group, as well as that of the (East Asian) tone fairly fluent group. The probability of obtaining any of these statistical differences by chance was less than one in a thousand. The performance of the tone fairly fluent group was also significantly higher than that of the nontone group, and also higher as a trend than that of the tone nonfluent group. The performance of the (East Asian) tone nonfluent group did not differ statistically from that of the (Caucasian) nontone group.

Most importantly, the performance of the (East Asian) tone nonfluent speakers was significantly poorer than that of the (East Asian) tone very fluent speakers, while at the same time their performance was not significantly different from that of the (Caucasian) nontone language speakers. So these findings indicate that the differences in performance between the groups were associated with language rather than ethnicity.

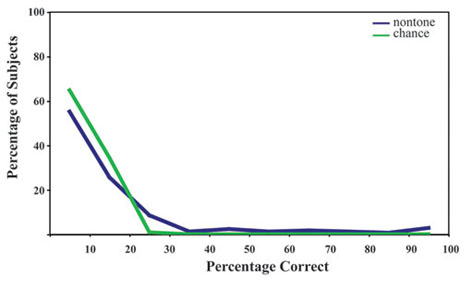

The strong relationship between the prevalence of absolute pitch and fluency in speaking a tone language is also reflected in the figures below. The first figure shows the relative distribution of scores of all the nontone language speakers in the study, together with the hypothetical distribution of scores expected from chance performance. Notice the striking similarity between these two plots, with a very slight increase in the prevalence of absolute pitch in the 90-100% region.

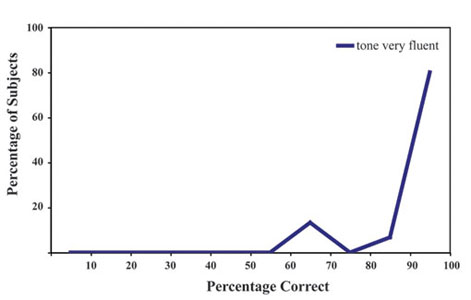

The second figure shows, in contrast, the relative distribution of scores in the tone very fluent group. As we can see, the performance of most of these subjects was in the 90-100% region. So this difference between the groups is very striking.

In a further analysis we divided the ’tone very fluent’ speakers into two groups: those who had been born in the U.S. or arrived in the U.S. before age 9, and those who had arrived in the U.S. after age 9, and we found that the performance of these two groups did not differ significantly.

Our present findings leave open the question of why some people who are not speakers of tone language acquire absolute pitch. Given our findings, those who are born into families of musicians would be at an advantage, since they would be exposed to musical notes together with their names very early in life – frequently before they began musical training. As for those who do not have this specialized exposure to music in infancy, we conjecture that they may have a critical period of unusually long duration, so that it extends to the age at which they can begin taking music lessons. At all events, our study shows that there is an overwhelmingly strong environmental influence on the probability of acquiring absolute pitch.

If you would like to listen to a full test designed as in this experiment and then view the answers, click here.